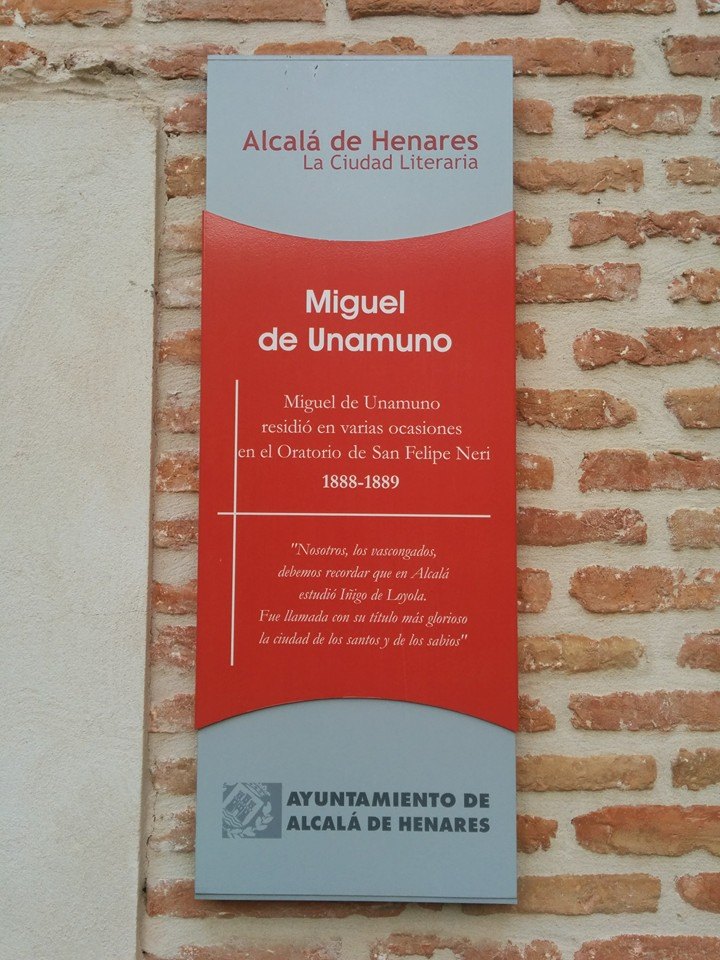

Antezana’s Hospital, side by side with Cervantes’ Birthplace Museum, is the oldest hospital of all Europe. Saint Ignacio de Loyola, founder of the Jesuit order, served in the hospital, as well as Miguel de Cervantes’ father, Don Rodrigo, bloodletting surgeon.

Nuestra Señora de la Misericordia de la Fundación de Antezana’s Hospital is also called by city inhabitants “hospitalillo” (Spanish diminutive that means “little hospital”) and owes his name to its little number of accommodations, 23 old ladies (12 until 2011). The hospital is also the oldest hospital of Europe with those characteristics, so it was founded in 1483.

Next to Cervantes’ House

Antezana’s Hospital is joined to Cervantes’ Birthplace Museum and it is possible to visit both places consecutively as wondering around calle Mayor, where the Jew medieval neighborhood was placed. Precisely, Antezana’s Hospital is opposite to the current passageway to what it was the Sinagoga Mayor.

Don Luis de Antezana, alderman of the small town of Guadalajara, and his wife, doña Isabel de Guzmán, from the noble house of Medina Sidonia founded the hospital for pilgrims, poor and sick people care. The creation of charity institutions to help poor people was a usual practice by rich and very religious families of Middle Ages.

Antezana’s Hospital has been ruled during the last 50 years by nuns of Siervas de María order, and, in 2006, its ruling passed on to Mensajeros de la Paz organization, founded by the famous Ángel García, which, not many years ago, received the Prince of Asturias award.

In order to rule it, its founders created a Council or board of nine honorable knights of Alcalá, which is still existing. Public administrations have invested funds during years for its improvement and restoration, as the one undertaken by the City Hall in 2010, when accommodations turned from 12 to 23.

Curiosity

The Antezana’s Hospital is considered as the oldest hospital in Europe that is still functioning.

No arcades

Antezana’s Hospital is placed in what it was the palace where its founders lived, who allocated an important part of the building to the institution, at calle Mayor, extended to the parallel road, calle Santiago. The Antezana family separated the Antezana’s Hospital from their own lodging, so they opened doors and windows to calle Mayor for the hospital.

The Antezana’s Hospital window and the Cervantes’ Birthplace Museum compound the only stretch in which calle Mayor does not hold arcades, owing to the presence, into the Hospitalillo façade, of huge balcony under a Mudéjar style wing, very much appreciated by experts. The wing is still visible nowadays, contrary to the balcony disappeared in 1800, when an neoclassical style was conferred to the façade.

Source of fighting

Antezana’s Hospital and its dependency annexed, with its own entrance, occupied the whole Antezana’s Palace since doña Isabel de Guzmán dead in 1506. This is a Gothic-Mudéjar style long building, in which a vaulted niche can be seen in the middle of two plants, with the image of Nuestra Señora de la Misericordia sculpted in stone, the Virgin that names the hospital.

What it is not possible to see today is a water font once set at the base, as the City Hall of Alcalá withdrew it in 1877 due to the fights and arguments that took place between those who wanted to drink fresh water. The consistory doubted between the withdrawal of the image or the font, deciding to eliminate the latter. However, after going through Antezana’s Hospital door there is a plaque talking about it existence. Besides, a sixteenth century column might be appreciated, embed into a wall, with the husband and wife coats of arms from Antezana and Guzmán families.

The first figure appreciated once inside the house is the square garden (originally rectangular), of popular style from Toledo, framing into the Spanish-Muslim tradition. The ground floor has, in some part of its extent, an open gallery supported upon lumbers and above, a corridor covered by a railing. The staircase to access the first floor, where fostered people lived, is also of Mudéjar style.

In the following restoring works of Antezana’s Hospital, coffered ceilings have been founded and restored, with lumbers in between founders’ coats of arms can be seen, as well as in Sala de los Caballeros or under the false ceilings discovered in 2011.

Saint Ignacio’s kitchen

There are two important historical characters related to Antezana’s Hospital: Saint Ignacio de Loyola and don Rodrigo de Cervantes, father of Don Quixote’s author. The former even has a chapel in his honor into the church though the latter worked in the place as a bloodletting surgeon, as an Alcalá’s tradition calls. However, there is no document into the City Hall that really proves such asseveration.

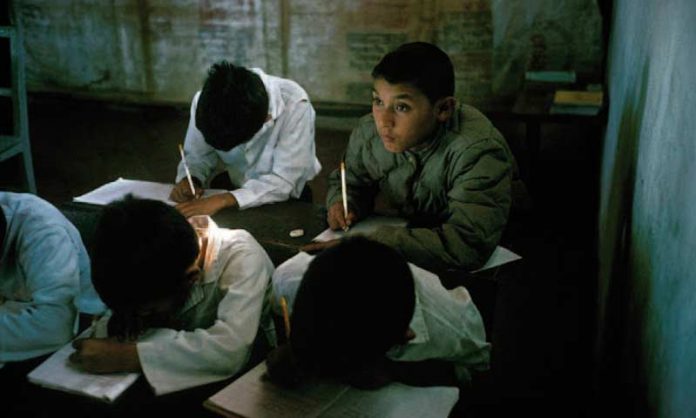

In the upper floor, next to the rooms, the kitchen where Saint Ignacio de Loyola worked as a scholar, is preserved as he used to work in before the Society of Jesus was created and got great importance for many papacies. He only stayed there the year between 1526 and 1527; moment in which he left the city due to the Spanish Inquisition prohibition of teaching without license, what he normally did on the well in Antezana’s Hospital garden.

The church and its organ

The old room occupied by the saint was turned into a chapel by the Society of Jesus in 1669 and placed inside the church. Within it, beside a portrait of him, it is possible to gaze at a great canvas representing the four miracles of Saint Ignacio, painted in 1658 by Pedro Valpuesta.

The Antezana’s Hospital church—with its direct access to the street—is composed by just one nave and precedes what it was Antezana’s family oratory. It has a barrel vault, and between its paintings, it stands out the “Inmaculada” painted by Martínez Montañés, in 1609. Here, the remains of the Antezana-Guzmán marriage are found, under a simple tombstone.

In the choir, there is an organ to accompany the service, the only of some antiquity in Alcalá de Henares, probably from the late of eighteenth century or beginning of nineteenth.

Additional information:

Image gallery:

gallery type=»rectangular» link=»file» ids=»5832,5833,5834,5835,5836,5839,13706,5838,17230,5837,5840,5842,5841,5843,5844″]

On video:

Useful information:

- Address: Calle Mayor, 46

- Telephone: +34 918 81 94 47

- Opening hours M-F: From 10:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. and from 4:30 p.m. to 8:00 p.m.

- Saturday openings: From 10:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. and from 4:30 p.m. to 8:00 p.m.

- Holiday openings: From 10:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. and from 4:30 p.m. to 8:00 p.m.

- Ticket price: Free entrance

Access from Madrid

- Renfe Cercanías railroads C-1, C-2 and C7A.

- Bus nº 223 (departure from Avenida de América Interchanger).

Where is it

View larger map

Phänomenta consta de una exposición compuesta por diversas actividades, donde los visitantes tienen la oportunidad de participar para descubrir la explicación de distintos fenómenos de la Naturaleza y de trucos matemáticos.

Phänomenta consta de una exposición compuesta por diversas actividades, donde los visitantes tienen la oportunidad de participar para descubrir la explicación de distintos fenómenos de la Naturaleza y de trucos matemáticos. Gran Caleidoscopio

Gran Caleidoscopio Rueda angular

Rueda angular Batería de mano

Batería de mano Cilindro de Vórtice

Cilindro de Vórtice Espejo cóncavo

Espejo cóncavo Péndulo de resonancia

Péndulo de resonancia Pelota flotante

Pelota flotante Serpiente de dados

Serpiente de dados Enanos

Enanos